Carer Teena Gates – A Day in the Life

“On a good day, dad’s digging daffodils and I’m boiling spuds and the whole world smells of sunshine and love. On a bad day, dad’s hiding under his duvet, shaking and crying, and afraid to come out because the whole world is scary and strange.”

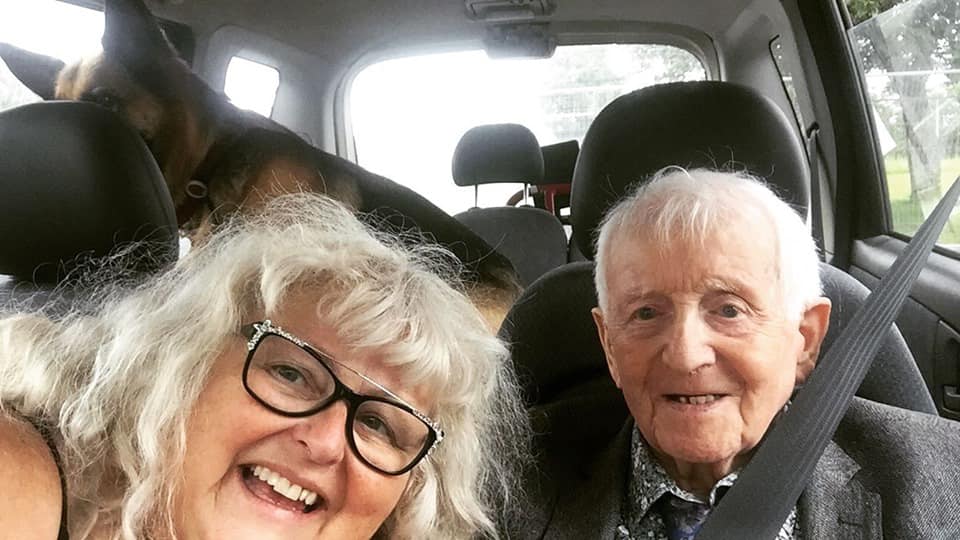

Journalist and Broadcaster Teena Gates is full-time carer for her elderly father, Terry, who was diagnosed with dementia last year. This is the story of her typical day.

Morning

It is pouring rain and my Dad, Terry, is outside digging for potatoes in the daffodil bed.

I have only been in the loo for two minutes max with the door open, but he got the slip on me and was out the door in a flash. I spot him through the large picture windows, as soon as I walk into the conservatory, and dash towards the door.

When I reach him, he’s damp, sweating and grinning from ear to ear.

“I’ll have the field finished in a minute,” he laughs.

I bite my tongue and congratulate him, walking back inside to put the kettle on. Do I leave him there? Hell, yes. He’s thrilled with himself. I can warm him up in a few minutes and change his clothes, hide the daffodil bulbs and boil some spuds and he’ll be the happiest man in Ireland.

That’s the beauty of having Dad at home. No nursing home or hospital would let a 94-year-old man “dig a field of potatoes in the rain” – nor should they. But at home, that’s exactly what my dad did this week.

Morning, afternoon and evening tend to merge into one in our house. Morning could be 10.00am when the carer comes to help get dad up and changed, while I nip out to walk the dog. Or it could be at 3.00am when the alarms go off because dad’s on the move. And again at 5.00am. And again at 7.00am. There could be three sets of sheets and pyjamas going into the washing machine by the time 10.00am arrives.

On a good day, dad’s digging daffodils and I’m boiling spuds and the whole world smells of sunshine and love. On a bad day, dad’s hiding under his duvet, shaking and crying, and afraid to come out because the whole world is scary and strange.

Afternoon

When dad’s carer arrived this afternoon, dad was already washed and fed and changed. He’d been questioning me manically all morning, asking questions I couldn’t answer. Why did I turn on the tap? Why did I have to boil the kettle? Are we all going to die? What’s going to happen to the dog when we die? When are we going to jail? Will we die in jail? Will we go to jail if we don’t die?

I have been deflecting, reassuring, and encouraging all morning, but our dog – “GoogleDog” – was looking at me with her ears down and I realised she was reading my tension. If the dog was getting that from my body language, what way was my dad feeling?

A couple of months ago when dad developed dementia, I would have been in tears and feeling guilty. Today, I realised I just needed a break. When dad’s carer arrived, I was out the door with the dog and off for a quick walk. That’s all it took. A breath of fresh air, a lung full of oxygen and a chance to let my shoulders drop and my mind rest. Just a moment. But it’s enough. Back to the house full of confidence and strength to turn it around, reassure him, change the mood.

Evening

This evening I’m in the conservatory with the large picture windows. It’s too dark now to see outside and instead I’m watching my own reflection in the glass. I’m on a conference call to Europe, working hard, participating in a vote. I’m tied to my keyboard and headphones and watching dad through the door that opens onto the kitchen.

I watch with amusement as he systematically unpacks the fridge and freezer, happily re-arranging everything in a heap on the floor. There’s not a thing in the world I can do, except continue my call, and prepare for the clean-up afterwards.

These days I don’t sweat the small stuff. The tidy ups can wait. The rules have changed.

I used to think I knew what being a carer was. I used to think I knew what 24/7 care meant. I didn’t have a clue. It means you never go to the toilet on your own again. It means you never close the door when you shower. It means you can’t meet a friend for coffee without a complicated cover system. It means working outside the home is practically impossible.

Yet all of these things are possible with support. So many of us just need a little help, to help us love and care for the ones we love and care for.

We’ve got to stop treating people with dementia as invisible, just because they can’t always tell you exactly what they’re feeling. How scary to be in a world that you don’t recognise any more, without the power to express that. If a person can’t speak to us in the way they used to, we’ve got to be the ones to bridge the gap. They haven’t disappeared, gone away, died. They are still Tessie, Terry or Tom and they deserve all the rights and entitlements they did before. We can’t just leave them behind.

Family carers don’t just care because we have to. We care because we love to. Talking about our needs and our family’s needs, it’s hard to get the message across about the joy. There is a lot of joy. There’s hardship, fear, financial pressure, stress; but there’s pure joy and delight and lots of fun and amusement. It’s easy to feel guilty talking about the need for support – because we don’t want to seem disloyal. Yet it’s a conversation that has to be had, because that support is what makes our loved ones able to thrive at home.

Ireland, during this Election campaign, please bring the message home: help us, to help ourselves, to help the ones we love.

Written by Teena Gates, January 2020

Contact your TD today

Please send a letter to your TD asking them to deliver on dementia in the next Programme for Government. It will only take 30 seconds. Click HERE

Alzheimer National Helpline

The Alzheimer Society of Ireland National Helpline is open six days a week Monday to Friday 10am–5pm and Saturday 10am–4pm on 1800 341 341 or [email protected]